Trees, people and zero-emission transport.

In April 2019 Newcastle City Council declared a Climate Emergency. This included a pledge to make Newcastle upon Tyne carbon neutral by 2030, taking into account both production and consumption emissions. The inclusion of consumption emissions means that the city’s target includes emissions from the manufacture of goods and services (such as food, clothing or electronic equipment) consumed by people living in the city.

In October 2019 the Council then announced the formation of a Climate Change committee to advise Cabinet and Council on the actions and resources required to meet the 2030 target, and a Net Zero task force to provide technical input to the committee. The Council will also work with other local authorities to set up a Citizens Assembly made up of residents from across the North of Tyne area.

The Climate Change Committee will publish a report in March 2020, which will set out how the city will meet the net zero target by 2030. This will be informed by the Council’s call for evidence for how to tackle climate change.

This blog sets out the SPACE for Gosforth response to that call for evidence, including eight ideas for quick wins that can be implemented immediately. Getting started quickly will be important, not least that by 31 January 2020 when the call for evidence closed the Council had already used up 303 (7%) of the 4,290 days available between 3 April 2019 when the target was set and 31 December 2030.

Dear Councillor Penny-Evans,

Re: Call for Evidence about climate change – January 2020

Thank you for the opportunity to contribute to the Council’s plans to make Newcastle upon Tyne carbon neutral by 2030. Our response specifically focuses on road transport, which based on the Council’s technical report makes up approximately 28% of the city’s emissions.

1. We welcome the Council’s target of carbon neutrality by 2030. Taking urgent action now, starting in 2020, will ensure Newcastle’s residents get the maximum benefit from the transition to low-carbon transport. These benefits include safer, quieter, less polluted streets, and more active travel means improved physical and mental health as well as being much cheaper than other modes of transport.

2. To achieve carbon neutrality by 2030, the steepness of carbon reductions in 2020-2022 is most important. This will require the Council to work at a much quicker pace than we have previously experienced. Taking four or five years to implement plans, as has been the case with the Council’s Streets for People initiative, will almost certainly guarantee that the target is missed. Ideally, work should be well underway by the middle of 2020 to achieve a 10% reduction by the end of the year.

3. Our response is guided by some principles.

a) Reducing road transport emissions can only be achieved by reducing the total number of miles driven, or by reducing average emissions per mile. More journeys by public transport can support this but only if there is a corresponding reduction in car journeys. More journeys by public transport with no reduction in car journeys will not reduce overall emissions.

b) The Council should prioritise and make the case for what works rather than limiting action only to what is popular. Changes that work are often found to be popular once implemented even if initially opposed: e.g. 70% of people in Stockholm supported road pricing after it was implemented even though prior to implementation a majority opposed it. The latest National Travel Survey also found 74% of people agreeing with the statement “Everyone should reduce how much they use their motor vehicles in urban areas like cities or towns, for the sake of public health”.

c) Timescales are key. To meet the 2030 target the Council will have to prioritise proven, quick to implement measures that will lead to a rapid reductions in green house gas emissions, starting in 2020. In our response we identify a number of quick wins that can be implemented in parallel to more detailed planning for future years. A draft list should be identified as soon as possible after completion of the consultation, ideally in February 2020, to give the Council the best possible chance to achieve a 10% reduction in 2020.

d) Exhorting people to change their travel behaviour has been ineffective in the past and there is no reason to think that this will be any different now. Only by changing the transport system in which people make their decisions will people make different decisions about how to travel. Crucially, this requires a rebalancing so that road design, investment and subsidies that have previously favoured private vehicles are revised and redirected so that active travel and public transport are more attractive than using a private car .

e) Modal shift away from driving towards the lower carbon alternatives presents an opportunity to deliver co-benefits e.g. public health, a stronger and more resilient local economy, strengthened communities, reduced road injuries and deaths. These co-benefits should be sought and highlighted.

f) We recognise that some of the key levers that could drive modal shift, e.g. fuel taxation, road pricing, carbon taxes, are in the hands of the UK government. However, it is also true that local authorities have other levers at their disposal such as planning permission, public space protection orders, control of the road network, licences and permits, traffic regulation orders, car parking controls and charges. The Council should be thinking about how it can use these now to achieve the reduction in emissions in 2020-2022 that will be necessary to meet the 2030 target.

4. Although our response focuses on local road transport, most of these principles also apply to other areas, and it is important to meet the Council’s target that the final plan is broadly based and covers all types of emissions including aviation and shipping as well as domestic and commercial emissions. For aviation the Council, as part owner of Newcastle Airport, should adopt a similar 2030 net-neutral target rather than the existing 28% by 2035 target. The Council should also engage with Highways England to ensure that its plans are consistent with meeting the Council’s targets.

5. The remainder of this response is organised into the following sections:

- Stopping current Council activities that will lead to increased green house emissions

- Quick wins for 2020-2022 – Changes the Council can implement now to reduce emissions

- Reducing the need to travel using the Council’s Planning Policy to prioritise net zero emissions

- Reducing emissions by reducing vehicle traffic and miles driven

- Supporting alternatives to driving

- Active Travel, walking and cycling

- Public transport – local buses

- Public transport – metro and local rail

- Public transport – ticketing

- Electric Vehicles

- Implementing the plan

6. The Council is still taking actions that lead to more driving and increased carbon emissions. Stopping such actions can be done at no or low cost and the Council should seek to ensure that all Councillors, Council employees and contractors visibly model the behaviour that they wish the rest of the city to adopt.

7. Stop road projects that aim to reduce congestion or increase traffic flow, such as at Haddricks Mill, as these will attract more traffic in an effect called induced demand. This adds to carbon emissions and air pollution while failing to deliver the anticipated time saving benefits that were the justification for the road expenditure. The Council should instead deliver only projects that will reduce vehicle miles driven or make journeys by public transport, bicycle or foot quicker or safer, and should retrain and redeploy transport engineers to deliver against these new priorities. By jettisoning this aspect of the transport department’s workload, resources will be freed up to help deliver climate transport actions at pace.

8. Stop increasing the amount of parking. The January 2020 decision to grant planning permission for an additional 550 new car parking spaces at the Forth Goods Yard shows a lack of joined up thinking. Even worse, this approach could be seen as cynical on behalf of the Council and risks deterring residents and the wider public from taking responsible action on client change. Residents need to be confident that measures introduced to tackle client change will be introduced equitably and will apply to all sectors of the community.

9. Stop promoting parking such as the Alive After 5 subsidised parking offer and the January 2020 promotional letters sent out by the Council’s Citypark Permits team including discounts and introductory offers. Again this shows at best a lack of joined-up thinking and at worst could be interpreted that the Council lacks a genuine commitment to climate change.

10. Stop accepting adverts for free parking on bus shelters and the Metro. This doesn’t even make any economic sense as encouraging people to drive rather than use public transport means fewer parking spaces for those that do need to drive.

Figure 1 Advertisement at Central Metro for free parking July 2019

Quick wins for 2020-2022 – Changes the Council can implement now to reduce emissions11. As well as stopping the activities outlined above, there are proven measures the Council can implement quickly. These measures are relatively cheap and do not rely on Government or other agencies to agree or implement.

12. Parking charges could be reviewed and increased, especially at locations that are well served by public transport. At such locations parking fees should be set so it is cheaper for a family of four to use public transport rather than drive and park, and so it is cheaper to park and ride from the city boundary rather than drive all the way into the centre. Charges should be levied on an hourly or daily basis rather than pre-paid for a longer period so that employees and commuters are not penalised if they take the bus one or two days a week.

13. Create low-traffic neighbourhoods by removing all non-stopping through-traffic on residential streets that are not classified as primary or secondary distributor roads. For Gosforth this could include the estates east and west of Gosforth High Street as well as roads like Hollywood Avenue and Hyde Terrace. This could be achieved simply and cheaply using the type of arrangement already in place at the north end of Alwinton Terrace. As well as reducing vehicle journeys, Waltham Forest also found this approach led to substantial increases in walking and cycling.

14. Use bolt-down kerbs to quickly create protected cycle lanes on main roads with minimal disruption and without substantial cost or re-engineering. These can be tweaked and upgraded if/when full funding is secured from central government. Priority locations would include where there is no choice but to use a main road and to assist with crossing main roads to get between low-traffic neighbourhoods.

15. Bus priority lanes ensure that buses run to time rather than getting stuck in traffic. These could be implemented on the Council’s designated public transport distributor routes there is space to do so and it wouldn’t compromise safety for other users. This would include most of the Great North Road but not Gosforth High Street where protected cycling lanes would make it safer and improve the experience for people walking and cycling, and enable people to shop and make local journeys by bike. Priority bus lanes and other traffic lanes should be kept to a maximum 3m width, as this is safer for all road users .

16. Speed limits should be reduced within the city boundary, with 20mph as the default. Many people think that higher speeds give a better fuel economy but that is not the case in a city where cars repeatedly have to slow down for junctions and to queue behind other traffic. In this scenario fuel economy is improved by reducing top speeds as it takes less energy and fuel to accelerate a vehicle to 20mph than it would to accelerate to 30 or 40mph. As above, lane widths should be kept to a maximum 3m width to encourage safer driving within the speed limit.

17. School Streets should be closed to traffic during drop off and pick up to improve safety, air quality and make it easier and more comfortable for children to walk or cycle to school. We suggest piloting this starting Big Pedal fortnight 2020, which is 22 April to 5 May .

18. The Council should model the behaviours it expects other employers and local organisations to adopt and advertise this widely. This might include how it sets and charges for parking for employees, secure parking for people cycling, discounted public transport offers, using cargo bikes where possible in preference to vehicles and ensuring ‘how to get there’ instructions prioritise walking, cycling and public transport rather than car parking,

19. Education – It is also important that the Council educate all Councillors, Council employees and local political parties about induced demand and disappearing traffic. A widespread lack of understanding of this issue has bedevilled progress on both climate change and reducing nitrogen dioxide in the city, as it leads people to cling to incorrect beliefs such as improving traffic flow will improve air quality and consequently fail to implement effective solutions. To illustrate how prevalent these incorrect beliefs are, in the last week both the Labour Cabinet Member for Employment and Culture has been quoted saying that “improving traffic flows at the front of the station we hope to cut carbon emissions” and a prospective Conservative Councillor for Gosforth has stated that he thinks traffic should move “smoothly and fast” . It is disappointing that this ignorance has taken place in what otherwise would have been very welcome announcements (Improvements to Central Station and raising awareness about illegal air pollution in Gosforth), and that, given that both the City Centre and Gosforth Air Quality Management Areas are 12 years old, that the Council has not previously addressed this issue so that Councillors, employees and local parties can effectively communicate with the public from an informed and realistic position.

Reducing the need to travel using the Council’s Planning Policy to prioritise net zero emissions

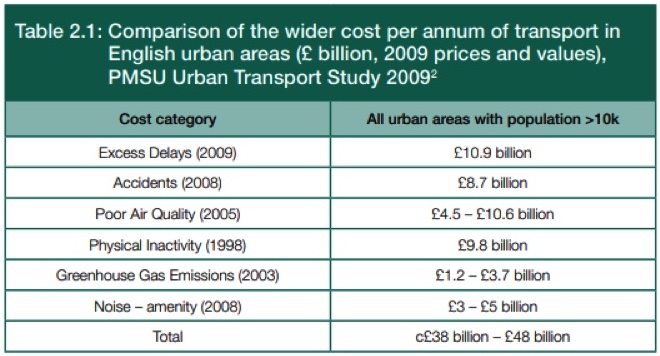

20. The current local plan has resulted in residential and commercial developments which generate road traffic due to their design and location making walking, cycling or public transport unrealistic options. In particular, low density developments can result in insufficient demand to make public transport viable while also making distances to facilities too long for walking or cycling. Our blog on one particular planning application illustrates the kind of problems that have been and are continuing to be built into our towns and cities and which create additional traffic with its associate problems including carbon emissions.

21. The Council should use the planning process to require a higher level of sustainability, increasing the requirements for new developments. If the developers object that this makes the development commercially unviable, then that is an indication that the development is unsustainable. Through a better planning process the Council can reduce the need for mobility and reduce car dependence.

22. The need for mobility can be reduced by ensuring that developments are better able to meet people’s need for services through accessibility rather than mobility i.e. have adequate provision for shops, schools, medical services etc. included in the development if not already easily accessible nearby without driving. Where developers have made commitments to provide services, the Council should take steps to ensure those commitments are honoured.

23. Car dependence can be reduced by having higher transport sustainability requirements for new developments:

- Residential developments to have sufficient secure cycle storage in line with number residents that the home is designed for, reduce permitted maximum distance from home to bus stop or metro for new developments, and be laid out in a way that is conducive to walking and cycling.

- Residential developments to be built with community amenities such as schools and doctors’ surgeries from the outset. If these amenities are not built, then no further planning permission should be granted until the amenities are built. The example of Newcastle Great Park, which is still lacking doctors surgeries, shops and middle and high school provision, shows how failing to build these essential services can reduce the quality of life of those who live in residential developments, and can lead to an increase of road traffic from the developments to surrounding communities, whose services are consequently put under pressure.

- For commercial and residential developments, require developers to fund the safe cycle infrastructure and walking routes needed to make the development accessible by active travel and ensure that the layout of the development is conducive to walking and cycling.

- For commercial developments, have an upper limit rather than a lower limit for the number of parking spaces provided.

24. The National Housing Audit report contains an analysis of both good and poor housing developments from a number of perspectives such as environment and community; place character; streets, parking & pedestrian experience; and detailed design and management. It identifies the following as transport aspects of developments that are often poor:

- Highways, bins and parking: The least successful design elements nationally relate to overly engineered highways infrastructure and the poor integration of storage, bins and car parking. These problems led to unattractive and unfriendly environments dominated by large areas of hard surfaces, parked cars and bins.

- Streets, connections and amenities: some design considerations were marked by a broad variation in practice nationally. These include how well streets are defined by houses and the designed landscape, and whether streets connect up together and with their surroundings. Also whether developments are pedestrian, cycle and public transport friendly and conveniently served by local facilities and amenities.

- Walkability and car dependence: The combination of the preceding factors influence how ‘walkable’ or car-dependent developments are likely to be. Many developments are failing in this regard with likely negative health, social and environmental implications.

25. The case study 12 in the report is a review of the Newcastle Great Park which was rated as poor overall and audit observations included:

- No local community facilities with the development

- The structure and form of the development includes a high number of cul-de-sacs accessed from key roads within the development

- The pedestrian environment is very poor: pedestrian links across and beyond the scheme are very circuitous.

- The townscape and landscape qualities for the scheme are poor

- The approach taken by the consortium was to establish a set of design principles that would guide the development of the different parcels of land by the different house builders: however, this approach has failed to deliver upon the aspirations for the site, and the outcomes for the overall pedestrian environment are poor.

26. The report includes recommendations to local authorities for planning and highways, and the Council should study this report and follow these recommendations to ensure that future housing developments are sustainable in terms of residential energy consumption and transport. The recommendations are:

- Set very clear aspirations for sites in advance: All design governance tools help to deliver better design outcomes and it is far better to use them then not. However the use of proactive tools that encompass design aspirations for specific sites – notably design codes – are the most effective means to positively influence design quality. Such tools give greater certainty for house builders and communities, but their use and the sorts of design ambitions that they will espouse should be made clear in policy, well in advance of sites coming forward for development.

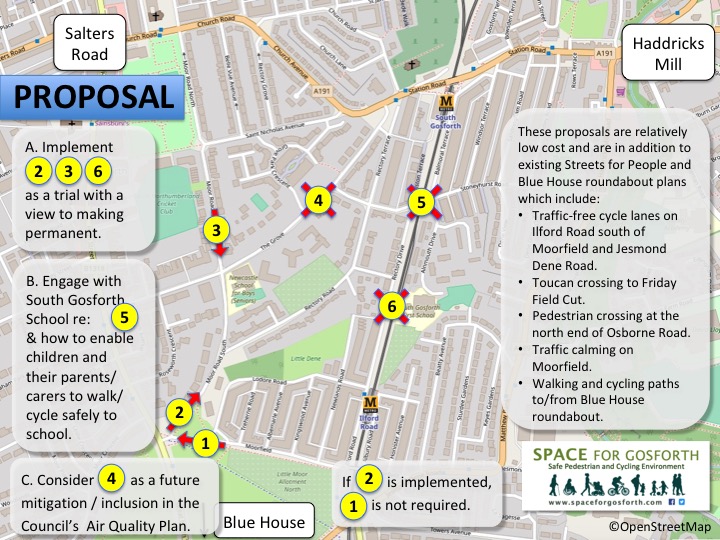

- Design review for all major housing schemes: Local authorities should themselves establish or externally commission a design review panel as a chargeable service and all major housing projects should be subject to a programme of design review. Advice on how to do this can be found in Reviewing Design Review [part of the report]

- Deal once and for all with the highways / planning disconnect: Highways authorities should take responsibility for their part in creating positive streets and places, not simply roads and infrastructure. Highways design and adoption functions should work in a wholly integrated manner with planning (development and management), perhaps through the establishment of multi-disciplinary urban design teams (across authorities in two tier areas), and by involving highways authorities in the commissioning of design review.

- Refuse sub-standard schemes on design grounds: The NPPF is very clear in its advice that “good design is a key aspect of sustainable development”. Consequently ‘poor’ and even ‘mediocre’ design is not sustainable and falls found of the NPPF’s ‘Presumption in favour of sustainable development’. Local planning authorities need to have the courage of their convictions and set clear local aspirations by refusing schemes that do not meet their published design standards.

- Consider the parts and the whole when delivering quality: Some well designed large schemes are being undermined by a failure to give reserved matters applications adequate scrutiny or through poor phasing strategies resulting in the delivery of disconnected parcels of residential development. Delivery of design quality requires both the whole and the parts to be properly scrutinised by local planning authorities at all stages during the design and delivery process.

Reducing emissions by reducing vehicle traffic and miles driven

27. In the SPACE for Gosforth blog ‘Air Quality – What Works?’ we summarised the measures that work to reduce air pollution. To a large extent the same measures will also be effective to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

28. In the Technical Report accompanying the Government’s UK Air Quality Plan it states that charging the most polluting vehicles is one of the most effective ways to reduce pollution. On the same basis, charging vehicles with the greatest greenhouse gas emissions is likely to be the most effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Council could use its proposed Clean Air Zone infrastructure to charge such vehicles.

29. A review by the University of British Columbia concluded that road pricing is most effective in reducing vehicle emissions. A research paper published in the American Economic Review came to the same conclusion and cites London’s congestion charge as having been effective in reducing traffic and carbon emissions.

30. A separate review by Public Health England showed that “driving restrictions produced the largest scale and most consistent reductions in air pollution levels, with the most robust studies.” The Council has substantial opportunity to implement driving restrictions quickly and cheaply, which could be through the implementation of low traffic neighbourhoods, bus priority lanes or stopping through traffic on city centre streets.

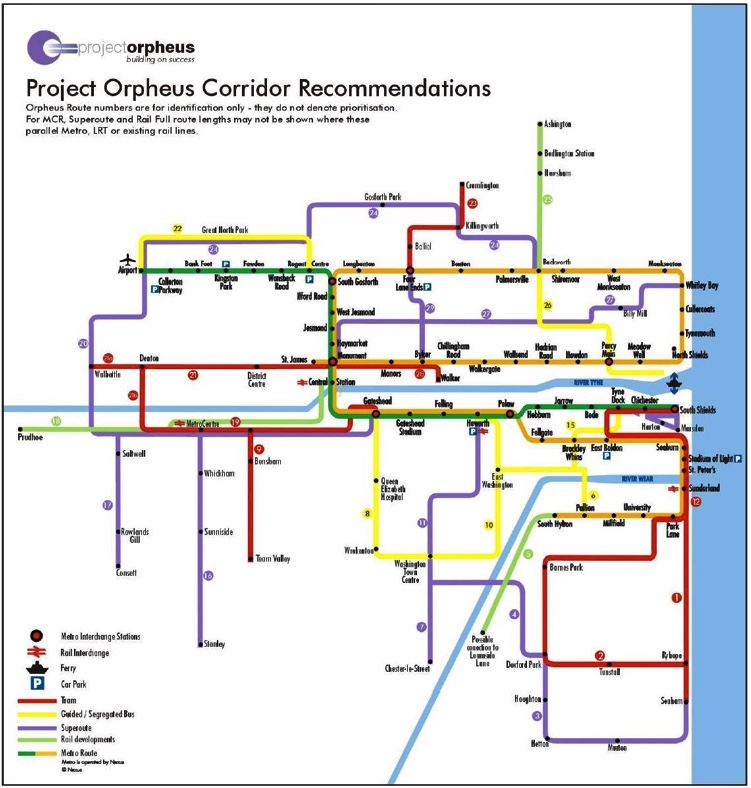

31. The Council’s Air Quality Status report includes an assessment of the measures currently being used to address air quality in Newcastle. All but four of these are classed low (or imperceptible) impact. The remaining four are: increasing public transport priority, low emission zone, higher parking charges and electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

32. The Government’s Air Quality Plan said about measures to optimise traffic flow that “there is considerable uncertainty on the real world impacts of such actions“. This is because rather than reducing air pollution, changes that are designed to improve or optimise flow can lead to more traffic (and more emissions). Other research has been more forthright, that having a goal of “free-flowing” traffic actually leads to more fuel consumption and emissions.

33. At Killingworth Road, Council data summarised in the SPACE for Gosforth blog ‘Roadworks, Air Quality and Disappearing Traffic’ illustrated quite clearly that driving restrictions (in this case in the form of road works) are effecting at reducing miles driven and that a substantial portion of traffic ‘disappears’ as a result, with a corresponding reduction in carbon emissions.

34. The Killingworth Road roadworks also showed the benefits of lower traffic levels on Hollywood Avenue, leading to cleaner air and a safer local environment for families and people walking and cycling. It also meant the bus was less likely to be caught up in traffic queues at the junction with the Great North Road.

35. For parking, Scientific American reports that ‘limiting parking through economic and policy changes has significantly reduced miles driven in 10 European cities.’

36. A Policy Brief by the University of California includes the conclusion that ‘that every 10 percent increase in parking price produces a reduction of approximately 3 percent in the demand for parking spaces.’

37. The price of parking relative to the cost of public transport is a factor that affects people’s choice of mode of transport. There is evidence that increasing parking charges is more effective than reducing fares in shifting journeys from driving to public transport .

“According to Liimatainen research in various cities around the world has found that car traffic is not necessarily reduced once public transport fees are waived, but rather when parking costs are increased.

“If a door-to-door journey on public transport takes as long as it does by car, half of commuters will take public transport and half will drive their cars. If the same trip by bus or train is one-and-a-half times longer, public transport use drops by 25 percent. If the journey is twice as long as in a car, then no one other than those who have no other means will use public transport,” Liimatainen said.”

38. Raising the cost of parking not only act to stimulates modal shift but also generates funds that can be invested to decarbonise transport. The implications of this are that the Council can achieve quick wins through

- Increase parking charges to a level that will influence people’s decisions about mode of transport

- End the provision of ‘Alive after Five’ free parking. This was introduced to kick-start the evening economy in Newcastle which is now well established and a subsidy that supports the most environmentally damaging form of transport can no longer be justified.

39. Research indicates that people choose their mode of transportation for urban trips based on the parking conditions at their origin and destination. The implication is that the council can achieve quick wins through reducing the number of parking spaces.

40. In the medium term, the Council can take other action on parking to encourage modal shift:

- Encourage employers with car parking to run schemes that build on the evidence about why it’s so hard to change people’s commuting behaviour” [See also here] . Light-touch nudges such as helping to set up car-pooling, providing free bus tickets or customized travel plans do not make a difference. Instead, companies should try other options such as giving employees the monetary equivalent of parking as a bonus, and then allowing employees to choose to use the bonus to pay for a parking spot or to keep the cash and choose alternative modes of travel.

- Implement a work place parking levy to change travel habits and generate funds to invest in transport infrastructure. A WWF report found that in its first three years, Nottingham’s levy raised £25.3 million of revenue, all of which has funded improvements in the city’s transport infrastructure, whilst contributing to a 33% fall in carbon emissions, and a modal shift which has seen public transport use rise to over 40%. Nexus has also previously shown support for using such revenue to expand the Metro via the Project Orpheus scheme (see below) .

41. An evaluation of Nottingham’s WPL concluded that the WPL and associated transport improvements have delivered mode shift away from commuting by car, and that the WPL has not negatively impacted on levels of inward investment and that there is some evidence to date that suggests the improved transport system facilitated by the WPL is attractive to potential business investors.

42. Additional evidence how achieving modal shift away from driving will be dependent on make driving less attractive comes from a case study of Stevenage which was designed with a Dutch-standards bicycle network but residents chose to drive because “critically, motorists in Stevenage were not constrained in any way”. John Pucher and Ralph Buehler’s influential report Making Cycling Irresistible says that “The most important approach to making cycling safe and convenient…is the provision of separate cycling facilities along heavily travelled roads and at intersections…” However, they add:

“separate facilities are only part of the solution. Dutch, Danish and German cities reinforce the safety, convenience and attractiveness of excellent cycling rights of way with extensive bike parking, integration with public transport, comprehensive traffic education and training of both cyclists and motorists, and a wide range of promotional events intended to generate enthusiasm and wide public support for cycling…The key to the success of cycling policies in the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany is the coordinated implementation of [a] multi-faceted, mutually reinforcing set of policies. Not only do these countries implement far more of the pro-bike measures, but they greatly reinforce their overall impact with highly restrictive policies that make car use less convenient as well as more expensive.”

43. General driving into the city centre could be reduced by making better use of park and ride from locations outside the urban core and on the edge of the city.

44. Freight related driving could be reduced by freight consolidation centres with a last mile delivery service.

Supporting alternatives to driving

45. Measures to discourage car journeys need to be accompanied by measures that enable much greater use of alternatives: public transport and active travel (walking & cycling).

Active Travel, walking and cycling

The wider benefits of active travel

46. An analysis undertaken for the Cabinet Office Strategy Unit’s study of urban transport showed that the measurable costs of urban transport of physical inactivity, congestion, road accidents and poor air quality are each in the region of about £10 billion per annum. Active travel has the potential to deliver benefits in all these areas.

47. This potential for active travel to help people to become more physically active or to stay physically active later in life is an important consideration in the context of the widespread inactivity and associated poor health that was quantified in the 2017 report from the British Heart Foundation

- 39% of UK adults (around 20 million people) are failing to meet Government recommendations for physical activity.

- Physical inactivity and low physical activity are the fourth most important risk factor in the UK for premature death

- Keeping physically active can reduce the risk of early death by as much as 30%.

48. Huge savings could be made for the NHS and social care by reducing the 40,000 early deaths from air pollution and the 200,000 deaths from cancer and heart disease annually not to mention the morbidity associated.

49. One of the messages of the 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change confirms the scientific evidence the active travel can deliver health benefits and how this can make a real difference to people’s lives

- “Additionally, the health benefits of increasing uptake of active forms of travel (walking and cycling) have been shown through a large number of epidemiological and modelling analyses. Encouraging active travel (particularly cycling) has become increasingly central to transport planning, and growing evidence suggests that bikeway infrastructure, if appropriately designed and imple¬mented, can increase cycling in various settings. A modal shift in transport could also result in reductions in air pollution from tyre, brake, and road surface wear, in addition to a reduction in exhaust¬ related particulates.”

- “I had an old bike sitting in the shed for years. After moving to a new job nearer home I decide to try cycling there. I began one gloriously sunny fresh spring morning. At first I wasn’t too sure of the route but that first day was really enjoyable. I arrived feeling energetic and ready. I wasn’t even very sweaty…. I did it again that summer on sunny days only. It felt so good. My confidence grew. Soon it became a routine even in less glorious weather! Now I cycle even in the rain and cold, but not the ice. It takes a bit longer than driving but I am getting my recommended 150 minutes of exercise every week, I’ve lost weight, I feel better in myself and my body and the satisfaction when I hear people complain about traffic jams is a secret joy. It’s been great and I wouldn’t go back.”

50. Active travel is a cheap or free option for the individual: an important consideration in a city with high levels of deprivation. Studies have looked at the internalised costs of cycling (time cost, vehicle operating costs, and personal health impacts) and the externalised costs (expenses in connection with congestion, noise, air quality and emissions, wider public health and accidents) and estimate the savings to society per mile cycled as 67p per mile, the difference between the 95p cost per mile driven is 95p and the 28p cost per mile driven

The potential for cycling in Newcastle

51. Newcastle is drier than Amsterdam and warmer than Copenhagen, two cities known for high rates of cycling.

52. The advent of e-bikes could make cycling viable for many more people as they make it easier to cycle more distance and over hillier terrain and to carry more weight, such as children or shopping. The boost effect means that people who are currently inactive or with existing health conditions can start to cycle with confidence, and that people who do cycle can carry on cycling with confidence despite any decline in health or fitness later in life.

53. The heavier loads that e-bikes can carry opens up new possibilities for freight. Local delivery and courier services could take advantage of the greater carrying capacity of e-bikes to use e-cargo bikes instead of cars or vans to deliver more and heavier items and in hillier areas. Such e-cargo bikes are already available and are starting to be deployed, for example Z-move in Newcastle and Gateshead delivering loads up to 200kg.

54. With the right approach, aiming for a significant increase in levels of cycling is realistic, provided that barriers to cycling are addressed.

More people want to cycle but are prevented by lack of safe infrastructure

55. This evidence shows that the lack of quality of cycling infrastructure, in particular routes that are convenient and feel safe for cycling, is a key barrier to people taking up cycling.

56. The national British Social Attitudes Survey 2013 identified a significant potential to increase the number of journeys being cycled instead of driven, but that the fear of traffic is a major barrier to people taking up cycling:

- When asked about the journeys of less than two miles that they now travelled by car

- 33% said that they could just as easily catch the bus

- 37% said they could just as easily cycle (if they had a bike)

- 40% of people agreed that they could just as easily walk.

- 61% of all respondents felt it is too dangerous for them to cycle on the roads, rising to 69% for women and 76% for those aged 65 and over.

57. In Newcastle, the Council’s Bike Life survey identified that there is support for better cycling infrastructure to enable people to cycle more often:

- 52% would like to start riding a bike, or could ride their bike more

- People want dedicated space for cycling: favouring on road physically separated space and traffic free routes away from roads over other forms of provision (bus lanes, on road painted lanes, shared pavements)

- Residents think safety needs to be improved for people cycling more than it does for people driving, walking or using public transport

- 74% of residents support building more protected cycle lanes, even when this can mean less room for other road traffic

58. In SPACE for Gosforth’s local survey sent to every address in the former East Gosforth, West Gosforth and Parklands Council wards

- 88% of people responding supported safe walking and cycling routes to schools

- 85% supported reducing traffic on residential streets

- 80% supported safer crossings

- 78% supported safe all age/ability cycle facilities on main roads.

Case studies of improved infrastructure achieving increased levels of walking and cycling

59. Waltham Forest enabled active travel by delivering “37 road filters to motor vehicles and two part-time road closures, the construction of 22km of segregated cycle lanes, 104 improved pedestrian crossings, 15 new pocket parks and the planting of more than 660 new trees. Speed limits have also been reduced to 20mph in most residential roads and some main routes.” This has led to a 13% increase in walking and 18% increase in cycling in the mini-Holland areas. A description of the plan and evaluation of the impact are available

60. “Ghent’s plan had imagined a cycling modal share of 35% by 2030, up from 22% in 2016. Instead, after an explosive 60% rise in cycle use, the target was reached last year [2019], 13 years earlier than planned for.”

61. Seville created a “network of completely segregated lanes, a full 80km (50 miles) of which would be completed in one go. … The average number of bikes used daily in the city rose from just over 6,000 to more than 70,000.“

62. “Macon Connects proved that if you build it (a bike network), they will ride. Bike counts along the pop-up network were 9.5 times (854%) higher during Macon Connects as compared to “normal conditions” when there is no bike infrastructure present.“

63. Barcelona traffic is restricted to major routes and only local traffic travelling at 10km/h can access so called ‘citizen spaces’

64. Other examples of bike lanes lead to an increase in cycling and boosting local businesses are included in the SPACE for Gosforth Can protected cycle lanes be good for business?

Making Newcastle safe for cycling

65. Investment is needed to provide safe, convenient and direct walking and cycling infrastructure, through a combination of protected cycle routes on busy roads such as distributor roads. Where streets are not required for through traffic measures need to be taken ASAP to reduce vehicle traffic so that streets are safer for people walking and cycling and buses are not delayed by congestion: e.g.

- in City Centre this means roads open for buses, delivery vehicles, walking and cycling but not to general motor traffic;

- on local residential streets that aren’t distributor roads, modal filters to prevent through vehicular traffic and create low traffic neighbourhoods ; and

- on distributor roads where well served by public transport and/or park and ride, bus priority measures and protected cycle routes.

66. The creation of low traffic neighbourhoods is key to making walking and cycling safe and attractive options. Waltham Forest has produced a ‘crib sheet’ for low traffic neighbourhoods and SPACE for Gosforth has developed a detailed proposal for a low traffic neighbourhood in Gosforth which would be quick & cheap to implement (using bollards or similar) , reduce driving and enable more walking and cycling. We expect that approach would be applicable to other areas in the city.

Figure 2 SPACE for Gosforth proposal for low traffic neighbourhood in East Gosforth

67. Higher rates of cycling will require more cycle parking in the city centre and at other key locations. Some city centre car parks should be converted to secure cycle parking, such as those available in the Netherlands. The main cycle park in Utrecht has nearly 20,000 spaces with 24*7 security, and is free for the first 24hrs and €1.50 per additional 24hrs thereafter.

Figure 3 Dutch underground dedicated cycle parking

68. In smaller homes, bike storage can be problematic. The council could provide on-street bike hangars for a small monthly feed. A number of other local authorities already do this including Lambeth, Southwark, Islington etc

Figure 4 Cycle hangar (Cyclehoop)

Figure 4 Cycle hangar (Cyclehoop)

69. Research shows that cyclists and walkers are three times as likely as motorists to be injured in icy conditions. De-icing pavements and cycle routes in winter will enable people to keep walking and cycling in winter and avoid injuries and would be consistent with policy to prioritise active travel. We have previously asked the council to prepare a target Winter Service Policy for walking and cycling networks with stakeholders. This should include routes to be cleared, effective approaches for how they are to be cleared and also consideration of funding, though work on the former should not be delayed while funding is sought. Other local authorities provide this service:

- York is running a pilot scheme, using special “baby-gritters” to keep 22km of York’s walk/cycle network ice-free

- Manchester grits “over 50km of pavements and cycle paths, including busy pedestrian areas in the city centre”

- Transport for London and London’s boroughs “ensure that the Cycle Superhighways and other cycling routes remain safe to use during the winter months.”

- Bristol grits “the Bath to Bristol and Castle park cycle paths”

- Edinburgh has a list of Cycleway Priority 1 routes which “will be the first to receive treatment whenever weather conditions dictate, and will be pre-treated where possible, when frost, snow or ice is forecast”

- Nottingham’s Winter Service Plan sets out priorities and response times for treating cycle ways.

- Cambridgeshire has “two quad bikes that treat over 50km of cycleways in Cambridge City and a dedicated team of around 70 volunteers who go out and salt the pavements.”

Public transport – local buses

70. Bus travel can be made more attractive by making bus journeys faster through improvements such as bus lanes, bus gates and intelligent traffic signals that detect approaching buses and prioritise their passage through the junction. Currently bus journeys are delayed due to the amount of time spent stationary at bus stops while people are buying tickets from the driver. New forms of ticketing would speed up bus journeys.

71. It is usually the case that the cost of bus journey for a single adult is similar to or greater than the marginal cost of driving i.e. parking and fuel. This provides an incentive to drive, particularly when two or more people are travelling together. Special rates for two or more people travelling together on public transport would make this an economic choice compared to driving.

72. The section below on ticketing has further proposals to support modal shift towards buses.

Public transport – metro and local rail

73. The capacity and extent of the metro system and local rail services could also be extended.

74. The Tyne and Wear Metro: The Tyne and Wear Metro system opened in 1980 and has had two major extensions: to Newcastle Airport in 1991 and to Sunderland in 1996. This compares poorly to the regular extensions of comparable continental systems such as the Stuttgart light rail system . Recently, the Metro has suffered problems of reliability, however hopefully these will be addressed by the introduction of new rolling stock from 2022. Although discussion of electric vehicles has centred on cars, in contrast to EVs the Metro is a tested and successful form of electric transport and should have a key role to play in future transport plans.

75. Expanding the Metro has the potential to provide an attractive alternative to driving, and should be considered both through extending the additional lines and adding new ones and in integrating the Metro with other forms of public transport. The original vision for the Metro was as part of a fully integrated public transport service, and this can still be seen in stations such as the Regent Centre which consist of both a Metro Station and a bus station and car park. Unfortunately, and despite evidence that the integrated approach was successful, deregulation ended this approach to local public transport.

76. In 2018 Mott MacDonald engineers produced a report on expanding the Metro and earlier there was the comprehensive Project Orpheus public transport plan for an integrated Metro, bus, light rail and local rail system, although this was not eventually funded. Had Project Orpheus been completed, Newcastle would most likely be better equipped to combat both Climate Change and nitrogen dioxide pollution as travellers both within and outside the city would have a viable option to the car for longer journeys.

Figure 5 Project Orpheus corridor recommendations

77. Project Orpheus and the Mott MacDonald report both show that there is the knowledge and vision to expand the Metro and local public transport, but lessons also can need to be learned from Project Orpheus about potential barriers. One problem with expanding the Metro is where land that has been earmarked for public transport system is reallocated for developments that preclude expanding public transport. We would recommend that such sites within the city are identified so that development on those sites is only permitted if it would be compatible with the expansion of public transport. Another issue is the lack of funding, however hopefully this can be addressed through the more positive recent attitude from central government to funding rail services. If not, then revenue from tolls and parking charges could be allocated to fund such developments. Comments from Nexus at the time of Project Orpheus suggest that such an approach is feasible.

78. Local rail: a number of Newcastle’s commuter towns served by rail services. These include Chester-le-Street, Corbridge, Cramlington, Durham, Hexham, Morpeth and Prudhoe. In general journey times to and from these stations are considerably faster than by road, particular during the morning and evening peak.

| Town | Journey time by rail (minutes) | Journey time by car at 5pm (minutes) |

| Chester-le-Street | 9 | 55 |

| Corbridge | 36 | 50 |

| Cramlington | 12 | 50 |

| Durham | 12 | 65 |

| Hexham | 31 | 60 |

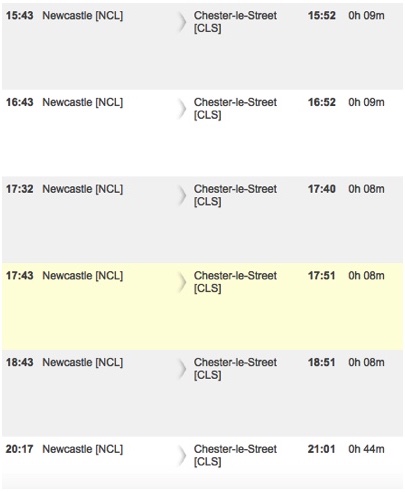

| Morpeth | 12 | 55 |

| Prudhoe | 18 | 55 |

79. Passenger experience on these routes varies considerably. Durham, which benefits from both National and Local Rail services, has frequent services during the day and evening and also benefits from modern trains, particularly on the intercity services. In contrast, the next station down the line, Chester-le-Street has a very limited service, as this image from National Rail Enquiries shows:

80. After the 20.17 train, the only other evening next train was 22.22. Consequently despite the short journey time, the lack of services prevents rail from being a viable option for commuting and for evening transport to the city. The situation in Cramlington is similar, where there are no services between between 18.00 and 22.20. Passenger experience of local services is also poor due to the continued use of outdated and unpopular Pacer trains. While Newcastle Council cannot take direct action to improve services or trains, they can lobby Government for replacing them and they can also persuade NE1, the local Chamber of Commerce, local businesses and unions to support modernising the railways by voicing the benefits to both employers and employees of better services. The recent announcement by the Government on reversing the Beeching cuts to the rail services and the reopening of the Ashington to Blyth line also shows that there is potential to increase the local rail network. We recommend that the Council supports the campaigns of SENRUG and other local rail groups to improve local services and to actively identify both railway lines that could be reopened and destinations such as Team Valley that are adjacent to a railway line and would benefit from a service to and from Newcastle. The Metro extension to Sunderland is an example of how a former railway line can be successfully returned to use.

81. Improving Central Station: Newcastle’s Central Station is one of its great buildings, and it forms a spectacular entrance to the city, especially when combined with other landmarks on and near the railway such as the High Level and King Edward bridges, Newcastle Castle, St Nicholas’ Cathedral and the Dene Street viaduct. The Council should seek to promote the attractive image of Central Station so that it is equally visible an entrance to the city as is the Tyne Bridge. The Council should also seek to improve passenger experience both within the station and when travelling beyond Central Station to destinations within Grainger Town and beyond.

82. Within Central Station: although Central Station is a spectacular building and benefits from facilities, more could be done to make it a welcoming place for passengers by improving waiting areas and by celebrating its history through introducing displays and artefacts to the stations. There have been two excellent exhibitions recently in the city connected to the railway (the Discovery Museum’s exhibition about the Rocket during the Great Exhibition of the North and the Laing Gallery’s inclusion of John Dobson’s own pictures of Grainger Town (including Central Station) during its Victoria and Albert Exhibition last year) so there is clearly the expertise within local museums and galleries to advise and assist with this. This would provide a useful counterweight to the regular displays on the Tyne Bridge that add prestige to the road links by signalling that the railway once again will play a significant role within the city.

83. Travelling beyond Central Station: Central Station has good walking links to Grainger Town, and the experience of pedestrians was improved as part of the Grainger Town project that revitalised the area adjacent to Central Station. Both Grainger Street and Collingwood Street (the two main streets leading from Central Station to Grainger Town) are architecturally of a very high quality and offer the potential for a traveller into the city to experience architecture of a calibre more commonly associated with cities such as Bath or Edinburgh. Journey times are also good as a pedestrian can reach Blackett Street in less than 10 minutes and the Haymarket in 15 minutes. However, pedestrian experience can be poor in places due to the volumes of traffic in Grainger Town, which is unpleasant and exposes the pedestrian to illegal levels of nitrogen dioxide and road danger. The current proposals to improve the city centre offer the potential to improve the pedestrian experience in Grainger Town, and this also important in persuading people to switch to rail when travelling through the city, as a short rail journey and a stroll through Grainger Town with its shops and cafes is a much pleasanter way to travel into the city than sitting in a traffic jam on the Western Bypass for an hour. Current proposals to add additional entrances to Central Station next to the Centre for Life and on Neville Street are welcome, as are future plans to add entrances to the rear of the station to the Stephenson quarter , however it is concerning that, as noted above, these proposals are linked to “improving traffic flows”, which (as explained above) is likely to increase rather than reduce carbon emissions.

84. Rather than improve facilities for motor traffic, proposals for Central Station should aim to improve cycle links within Grainger Town to make the combination of cycling and rail a viable travelling choice for those travelling to and from the station as this has the potential to increase the number of people able to travel by train.

85. Manors Station: Newcastle’s second rail station, Manors, is currently neglected and revitalising it should be part of the climate strategy. Sadly the original John Dobson buildings have now been destroyed and Manors is not an attractive station.

Figure 6 Manors station

86. Despite its neglect, Manors is well-positioned to serve the east of the city centre and to be a gateway to the business parks that surround it, Northumbria University and the Quayside Offices. The following steps could be taken to promote the use of Manors Railway Station:

- Ensuring it is listed as a Newcastle station (e.g. Manors NCL) on National Rail Enquiries so that those seeking to travel to the city are aware of it. At present it is just listed as Manors.

- Putting signs on the Central Motorway and using the Central Motorway television screen advertising board to advertise its location as an alternative to driving.

- Requesting NE1 to regularly advertise and promote rail services to Central Station and Manors Station via social media and their magazine in a similar manner to how they have promoted Alive after 5.

- Extending local rail services from destinations such as Chester-le-Street to Manors Station.

- Improving amenities for passengers on the station, for example by introducing a trading concession so that the station is manned and consequently feels more friendly.

- Improving walking and cycling routes from Manors Station as many are currently of poor quality. A particular focus should be safe and attractive walking routes to the Quayside and Northumbria University.

Public transport – ticketing

87. The variety of tickets on offer for local rail and other public transport compares poorly with that on offer in other countries. Greater use of public transport could be encouraged by cheaper fares, particularly at off peak times. As deregulation is an obstacle to integrated ticketing across the region, the Council should seek to work together with NE1, the Chamber of Commerce and local businesses and unions to put pressure on public transport operators to adopt sensible ticketing policies. The following suggestions would vary the offer of tickets and encourage more people to use public transport:

- “Carnet” style tickets where passengers can get a discount for buying several tickets (e.g. 10) for the same route. This would benefit passengers who take a regular journey, but do not travel frequently enough to buy a weekly pass

- Part-time worker travel cards

- Discounted family tickets. The current offer for free child travel on the Metro is welcome, but this is only for children under 11. There is a need for cheap family tickets for children under 16. At present, this is too expensive so many families will drive.

- Cheap off peak travel. Germany’s Quer-durch-land tickets are a good example of how passengers can save money by travelling together as a group on off-peak local services . While this ticket is designed for a larger region than Newcastle, the model could be adopted for local services, for example to encourage groups to travel into the city by public transport during the evening rather than driving.

- Free or discounted travel for children. Transport for London’s Zip Oyster card 5-10 and 11-15 are examples of this. This would be particularly useful in managing traffic to Newcastle’s private schools and also to community schools that serve communities at a distance from the school (for example Gosforth Academy is the feeder high school for the Great Park and for Dinnington).

- Free or discounted travel for school groups. Transport for London has an example of this.

- Oyster cards to encourage people to travel on a range of services and to use public transport discounts.

Electric Vehicles

88. Electric vehicles (EVs) are not zero greenhouse gas emissions vehicles, and in addition they emit particulate air pollution at levels similar to internal combustion engine vehicles. Taking into account manufacture as well a driving, the whole life greenhouse gas emissions of a Nissan Leaf are still about 50% of that of an internal combustion engine vehicle. While driving is less damaging if the vehicle is an EV, deep reductions cannot be achieved quickly by relying on a shift from conventional vehicles to EVs but will require modal shift from all forms of private driving to even lower or zero emissions forms of transport wherever possible: public transport and active travel (walking and cycling).

89. In our submission to the 2017 Business Energy & Industrial Strategy parliamentary select committee we recommended against the introduction of ‘on-the-road’ measures that incentivise or privilege EV drivers over other drivers, such as permission to use bus lanes or contraflows that are not open to all vehicles or reduced charges for parking. The council should reject such measures for several reasons:

- ‘on-road’ privileges would undermine policy of modal shift towards public transport, walking and cycling. efforts to achieve modal shift towards public transport and walking and cycling and so would impede progress in carbon reductions and the delivery of the co-benefits of modal shift such delays due to congestion, the risk of injury or death from collisions, and the personal and public health consequences of physical inactivity and of particulate air pollution.

- Different driving rules for EVs would also create confusion and present an increased safety risk for other road users especially the most vulnerable road users, pedestrians and cyclists.

- Whether or not such measures were effective in stimulating EV uptake, the need for them would disappear overtime as EV usage increases, but it would be politically difficult to withdraw these perks once drivers had become used to them and this would mean an ongoing conflict between actions to promote EVs and actions to promote modal shift.

90. In a subsequent 2018 submission we addressed the impact that the poor placement of on-street EV charging stations could have on pedestrians. EVs will bring some benefits, but it should not come at the expense of people more generally or the quality of the urban realm. For these reasons, recharging equipment should be placed so that it does not impinge upon safe and convenient movement of pedestrians on the pavement, should avoid placement on the pavement and avoid any trip hazards due to trailing cables when in use. Ideally charging equipment should be placed in the carriageway, not on the pavement.

91. While EVs can play a role in reducing carbon emissions, they are a new and speculative technology and consequently may not bring all of the anticipated benefits. The Council should rely on more established forms of transport where there is clear evidence to support the desired results. A previous example of how reliance on new technology can fail to deliver can be found in the 2006 Air Quality Report , where the adoption of Euro III and Euro IV standards for buses was thought to lead to “significant progress towards achieving the objectives” of lowering levels of nitrogen dioxide. This reliance on improving engine technology was discredited by the dieselgate scandal and the Council has failed to reduce nitrogen dioxide to within the legal limits. Additionally electricity as a replacement fuel should not solely be considered with regard to EVs that are cars: whilst electricity is a new technology for cars, it is a mature technology for the railway and revitalising the Tyne and Wear Metro and local rail services are further discussed below.

Implementing the plan92. The council need to develop and communicate a vision of a socially and environmentally resilient future and the benefits that people will experience from as we move to a more sustainable travel system

93. The net zero target for 2030 should be supplemented by a target for each year in the 2020s so that progress can be monitored and reported annually and corrective actions taken promptly if needed.

94. The Council should ensure that all its strategies, policies and working practices fully reflect the need to deliver the net zero carbon target and consider the infrastructure and the use of it as a holistic system. This should include:

- Aligning strategic investment decisions to address fully the requirement for demand management, and a substantial increase in the proportion of journeys made by active travel, and a much greater role for public transport.

- For such roads investment that is made as part of the above, a presumption in favour of investment to future proof existing road infrastructure and to make it safer, resilient and more reliable rather than increase road capacity or reduce travel time.

- Training for staff to support new transport priorities and goals, including effective community engagement

95. The pace of delivery of road and cycle infrastructure in recent years is not sufficient for the challenge of meeting the 2030 target. The processes used should be changed to increase the pace of decision making and delivery: implement quickly, trial & tweak, rather than carry out long consultations.

96. To provide people with a safe, easy to use and comfortable cycling experience, adopt best practice in design and construction of cycling infrastructure, for example as documented in the London Cycling Design Standards 2014.This documents six core outcomes which ‘together describe what good design for cycling should achieve: Safety, Directness, Comfort, Coherence, Attractiveness and Adaptability. These are based on international best practice and on an emerging consensus in London about aspects of that practice that we should adopt in the UK

97. The council should improve consultations, information sharing and community engagement and work with local people who have ideas of how to make simple changes in their area. There should be regular meetings with stakeholders and regular progress reporting against actions.

We support the target of achieving net-zero by 2030 and hope that the Council will be inspired to take bold action to rise to the this challenge and confidently pursue allied benefits of a cleaner, safer, healthier and city.

Yours sincerely,

SPACE for Gosforth

www.spaceforgosforth.com

- https://usa.streetsblog.org/2017/07/06/urban-myth-busting-congestion-idling-and-carbon-emissions

- https://www.ted.com/talks/jonas_eliasson_how_to_solve_traffic_jams/

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/858253/national-travel-attitudes-study-wave-2.pdf

- https://hbr.org/2019/12/why-its-so-hard-to-change-peoples-commuting-behavior

- https://www.newcastleairport.com/about-your-airport/masterplan/masterplan-2035-summary/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Induced_demand

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/forth-yards-station-arena-homes-17558909

- https://walthamforest.gov.uk/content/increased-levels-walking-and-cycling-extend-life-expectancy-waltham-forest-residents-least

- https://www.citylab.com/design/2014/10/why-12-foot-traffic-lanes-are-disastrous-for-safety-and-must-be-replaced-now/381117/

- http://www.20splenty.org/do_emission_increase

- https://hackney.gov.uk/school-streets

- https://bigpedal.org.uk

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/newcastle-central-station-new-entrance-17657512

- https://www.facebook.com/GosforthMatters/videos/2512154069029612/

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/gosforthbusinesspark/

- Cycle storage has been also identified as helpful as long ago as the 2006 Air Quality Planhttps://newcastle.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Air%20Quality%20Action%20Plan%20-%20City%20Centre.pdf

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/newcastle-great-park-gp-surgery-15759547

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/wheres-town-centre-people-great-14430706

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/great-park-first-school-2022-17184283

- http://placealliance.org.uk/research/national-housing-audit/

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/air-quality-what-works/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/air-quality-plan-for-nitrogen-dioxide-no2-in-uk-2017

- https://phys.org/news/2017-10-road-pricing-effective-vehicle-emissions.html

- https://www.citylab.com/transportation/2011/10/only-hope-reducing-traffic/315/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/improving-outdoor-air-quality-and-health-review-of-interventions

- https://www.newcastle.gov.uk/services/environment-and-waste/environmental-health-and-pollution/air-pollution/air-quality

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/air-quality-plan-for-nitrogen-dioxide-no2-in-uk-2017

- https://walkablestreets.wordpress.com/1993/04/18/does-free-flowing-car-traffic-reduce-fuel-consumption-and-air-pollution/

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/roadworks-air-quality/

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/reducing-parking-cut-auto-emission/

- https://ww3.arb.ca.gov/cc/sb375/policies/pricing/parking_pricing_brief.pdf

- https://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/news/free-of-charge_public_transport_isnt_free_finnish_experts_say/11147862

- http://www.etcproceedings.org/paper/the-impact-of-car-parking-policies-on-greenhouse-gas-emissions

- https://hbr.org/2019/12/why-its-so-hard-to-change-peoples-commuting-behavior

- https://www.treehugger.com/cars/how-will-we-ever-get-people-out-cars.html

- https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2016-12/nottingham%20case%20study%20-%20Workplace%20parking%20levy.pdf

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/call-to-charge-car-drivers-1666823

- https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/Evaluating_the_impacts_on_traffic_congestion_and_business_investment_following_the_introduction_of_a_Workplace_Parking_Levy_and_associated_transport_improvements/9453812

- https://roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com/stevenage/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01441640701806612

- https://www.cyclinguk.org/sites/default/files/document/migrated/news/activetravelstrategy.pdf

- https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32596-6/fulltext

- https://www.sustrans.org.uk/our-blog/opinion/2016/march/can-we-put-a-figure-on-the-value-of-cycling-to-society/

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/drier_than_amsterdam/

- https://www.zmove.uk/

- https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/british-social-attitudes-survey-2013

- https://www.sustrans.org.uk/media/2946/bike-life-newcastle-2017.pdf

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/your-streets-your-views-survey-results/

- https://walthamforest.gov.uk/content/increased-levels-walking-and-cycling-extend-life-expectancy-waltham-forest-residents-least

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0965856417314866

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jan/20/how-a-belgian-port-city-inspired-birminghams-car-free-ambitions

- https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/jan/28/seville-cycling-capital-southern-europe-bike-lanes

- http://www.newtownmacon.com/macon-connects/

- https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/17/superblocks-rescue-barcelona-spain-plan-give-streets-back-residents

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/bike-business/

- https://camdenresidentsbath.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Low-Traffic-Active_Liveable_Healthy-Neighbourhoods-2-1.pdf

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/east-gosforth-lcwip/

- The temporary concrete blocks on Salter’s Bridge during the Killingworth Rd works provide an example of how quick and simple interventions can change traffic levels in a neighbourhood

- https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/parking-transport-and-streets/cycling/cycle-parking-scheme-guide

- https://southwarkcyclists.org.uk/cycle-parking-guide/

- http://islingtontribune.com/article/2-a-week-a-fair-price-for-a-bike-hangar

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2020/jan/24/weatherwatch-walkers-and-cyclists-first-in-yorks-winter-safety-plans

- https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/snow-and-ice/

- https://www.theguardian.com/news/2020/jan/24/weatherwatch-walkers-and-cyclists-first-in-yorks-winter-safety-plans

- http://www.manchester.gov.uk/directory/154/gritting_route

- https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/media/press-releases/2017/january/tfl-and-london-boroughs-prepared-for-wintry-weather

- https://www.bristol.gov.uk/streets-travel/roads-pavements-winter

- http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/info/20047/severe_weather/1139/priority_system_for_winter_gritting_routes

- http://www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/winter

- https://www.cambridgeshire.gov.uk/residents/travel-roads-and-parking/roads-and-pathways/gritting-roads-cycleways-and-paths/

- https://www.nexus.org.uk/history/how-metro-was-built

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuttgart_S-Bahn or https://www.s-bahn-stuttgart.de/s-stuttgart/ueber_uns/Ein-Blick-in-die-Vergangenheit-4384124 (this is a more detailed history in German).

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/metro-new-trains-live-updates-17641807

- https://www.nexus.org.uk/history/landmarks-urban-transport

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/metro-nexus-expansion-tyne-wear-15243313?fbclid=IwAR2-9D6hZwtROdPH5MmybzfqM41kPFZOWU044GRJ7tYzFSFlPMnEDtC1J9M

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jan/26/northern-rail-to-be-renationalised-and-some-beeching-closures-reversed

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/call-to-charge-car-drivers-1666823

- http://www.senrug.co.uk/Newcastle-CramlingtonMorpethLocalService

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/national-rail-museum-now-pacer-17484984

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jan/26/northern-rail-to-be-renationalised-and-some-beeching-closures-reversed

- http://www.senrug.co.uk/our-campaigns

- see for example https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/rugby-world-cup-sign-being-10369760

- https://www.gillespies.co.uk/projects/grainger-town-project

- https://newcastle.gov.uk/our-city/transport-improvements/city-centre-improvements

- https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/newcastle-central-station-new-entrance-17657512

- https://www.nationalrail.co.uk/stations_destinations/MAS.aspx

- https://www.thameslinkrailway.com/tickets/ticket-types-explained/carnet-tickets

- https://www.nexus.org.uk/metro-child-single

- https://www.european-traveler.com/germany/save-cheap-travel-throughout-germany-train-ticket/

- https://tfl.gov.uk/fares/free-and-discounted-travel/5-10-zip-oyster-photocard?intcmp=55572

- https://tfl.gov.uk/fares/free-and-discounted-travel/11-15-zip-oyster-photocard?intcmp=55575

- https://tfl.gov.uk/fares/free-and-discounted-travel/travel-for-schools?intcmp=54736

- https://tfl.gov.uk/fares/free-and-discounted-travel

- https://www.carbonbrief.org/factcheck-how-electric-vehicles-help-to-tackle-climate-change

- http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/business-energy-and-industrial-strategy-committee/electric-vehicles-developing-the-market/written/68918.pdf

- http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/business-energy-and-industrial-strategy-committee/electric-vehicles-developing-the-market-and-infrastructure/written/83250.pdf

- https://newcastle.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Air%20Quality%20Action%20Plan%20-%20City%20Centre.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volkswagen_emissions_scandal

- https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/publications-and-reports/streets-toolkit#on-this-page-1

The Newcastle Liberal Democrats have published their submission which you can access via this link

https://www.dropbox.com/s/o2vbdmpy5brhzhp/Submission%20to%20the%20Newcastle%20Climate%20Convention%20from%20the%20Newcastle%20Liberal%20Democrat%20Group.pdf

The Newcastle Green Party have published their submission which you can access via this link

https://newcastleupontyne.greenparty.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/40/2020/02/Response_to_Newcastle_City_Council_Climate_Change.pdf